Click here for previous entries

HAPPY NEW YEAR 2021

(An acrostic poem where the first letter of each line spells out the title of the poem)

Heaven’s gift of another year

As the old departs and the new is born,

Plans for a future and a hope

Preparing us for each new dawn.

Yesterday has gone forever,

New days and ventures lie ahead,

Even darkness turns to light

When we make the Lord our head.

Yielding to the Holy Spirit

Ever mindful that He’s there,

As we live our lives before Him

Rejoicing in His loving care.

By Megan Carter

15th July St Swithun (or Swithin) - saint for a rainy day

St Swithun is apparently the saint you can blame for rainy summers. It is said that if it rains on his special day, 15th July, it will then rain for 40 days after that. It all began when Swithun was made Bishop of Winchester in 852 by King Ethelwulf of Wessex. It was an important posting: Winchester was the capital of Wessex, and during the 10 years Swithun was there, Wessex became the most important kingdom of England.

during the 10 years Swithun was there, Wessex became the most important kingdom of England.

During his life, instead of washing out people’s summer holidays, and damping down their spirits, Swithun seems to have done a lot of good. He was famous for his charitable gifts and for his energy in getting churches built. When he was dying in 862, he asked that he be buried in the cemetery of the Old Minster, just outside the west door.

If he had been left there in peace, who knows how many rainy summers the English may have been spared over the last 1000 years. But, no, it was decided to move Swithun. By now, the 960s, Winchester had become the first monastic cathedral chapter in England, and the newly installed monks wanted Swithun in the cathedral with them. So finally, on 15 July 971, his bones were dug up and Swithun was translated into the cathedral.

That same day many people claimed to have had miraculous cures. Certainly everyone got wet, for the heavens opened. The unusually heavy rain that day, and on the days following, was attributed to the power of St Swithun. Swithun was moved again in 1093, into the new Winchester cathedral. His shrine was a popular place of pilgrimage throughout the middle ages. The shrine was destroyed during the Reformation and restored in 1962. There are 58 ancient dedications to Swithun in England.

7th June Trinity Sunday, celebrating our God who is Three Persons

Trying to explain the doctrine of the Trinity has kept many a theologian busy down the centuries. One helpful picture is to imagine the sun shining in the sky. The sun itself – way out there in space, and unapproachable in its fiery majesty – is the Father. The light that flows from it, which gives us life and illuminates all our lives, is the Son. The heat that flows from it, and which gives us all the energy to move and grow, is the Holy Spirit. You cannot have the sun without its light and its heat. The light and the heat are from the sun, are of the sun, and yet are also distinct in themselves, with their own roles to play.

The Bible makes clear that God is One God, who is disclosed in three persons: Father, Son (Jesus Christ) and Holy Spirit. For example:

Deuteronomy 6:4: ‘Hear O Israel, The Lord our God, the Lord is one.’

Isaiah 45:22: ‘Turn to me and be saved… for I am God, and there is no other.’

Genesis 1:1-2: ‘In the beginning God created…. and the Spirit of God was hovering…’

Judges 14:6: ‘The Spirit of the Lord came upon him in power…’

John 1:1-3: ‘In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was with God in the beginning. Through Him all things were made; without Him nothing was made that has been made.’

Luke 24:49 actually manages to squeeze the whole Trinity into one sentence. Jesus tells His disciples: ‘I am going to send you what my Father has promised; but stay in the city until you have been clothed with power (the Holy Spirit) from on high.’

In other words, the sun eternally gives off light and heat, and whenever we turn to its brilliant light, we find that the warmth and life there as well.

8th May - Julian of Norwich, a voice from a distant cell

by Canon David Winter

Many years ago, studying English literature at university, I was intrigued to be introduced to the work of Julian of Norwich. She was writing at the end of the 14th century, when our modern English language was slowly emerging from its origins in Anglo-Saxon and Middle English.

Our lecturer was mainly concerned with her importance in the history of the language (she was the first woman, and the first significant writer, to write in English). But I was more intrigued by the ideas she was expressing. She was an anchoress – someone who had committed herself to a life of solitude, giving herself to prayer and fasting. St Julian’s, Norwich was the church where she had her ‘cell’.

Her masterpiece, Revelations of Divine Love, reveals a mystic of such depth and insight that today up and down Britain there are hundreds, possibly thousands, of ‘Julian Groups’ who meet regularly to study her writings and try to put them into practise.

She is honoured this month in the Lutheran and Anglican Churches, but although she is held in high regard by many Roman Catholics, her own Church has never felt able to recognise her as a ‘saint’. This is probably because she spoke of God as embracing both male and female qualities. Revelations is an account of the visions she received in her tiny room, which thousands of pilgrims visit every year.

Her most famous saying, quoted by T S Eliot in one of his poems, is ‘All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.’ These words have brought comfort and strength to many a soul in distress.

23 April - St George: our patron saint who isn’t English

It’s perhaps typical of the English that they should have a patron saint who isn’t English, about whom next to nothing is known for sure, and who may not have existed at all. That didn’t stop him being patriotically invoked in many battles, notably at Agincourt and in the Crusades, and of course it is his cross that adorns the flags of English football fans to this day.

It’s most likely that he was a soldier, a Christian who was martyred for his faith somewhere in Palestine, possibly at Lydda, in the early fourth century. At some point in the early centuries of the Church he became associated with wider military concerns, being regarded as the patron saint of the Byzantine armies. There is no doubt that he was held as an example of the ‘godly soldier’, one who served Christ as bravely and truly as he served his king and country.

The story of George and the dragon is of much later date and no one seems to know where it comes from. By the middle ages, when George was being honoured in stained glass, the dragon had become an invaluable and invariable visual element, so that for most people the two are inseparable. Pub signs have a lot to answer for here: ‘The George and Dragon’.

However, it’s probably more profitable to concentrate on his role as a man who witnessed to his faith in the difficult setting of military service, and in the end was martyred for his faithfulness to Christ.

The idea of the ‘Christian soldier’ was, of course, much loved by the Victorian hymn-writers - ’Onward, Christian soldiers!’ The soldier needs discipline. The heart of his commitment is to obedience. The battle cannot be avoided nor the enemy appeased. He marches and fights alongside others, and he is loyal to his comrades. In the end, if the battle is won, he receives the garlands of victory, the final reward of those who overcome evil.

St George’s Day presents a challenge and an opportunity. The challenge is to distance the message of his life from the militarism and triumphalism that can easily attach itself to anything connected to soldiers and fighting. The opportunity is to celebrate the ideal of the ‘Christian soldier’ - one who submits to discipline, sets out to obey God truly, does not avoid the inevitable battle with all that is unjust, wrong and hateful in our world, and marches alongside others fighting the same noble cause. Discipline, obedience, courage, fellowship and loyalty - they’re not the most popular virtues today, but that doesn’t mean that they don’t deserve our gratitude and admiration.

5 – 12 April - Passion Week

The events of Easter took place over a week, traditionally called Passion Week.

It began on Palm Sunday. After all his teaching and healing, Jesus had built a following. On the Sunday before he was to die, Jesus and his followers arrived at Jerusalem. The city was crowded. Jewish people were arriving from to celebrate Passover. This commemorates how they had escaped from slavery in Egypt nearly 1,500 year earlier.

Jesus rode into the city on a young donkey. He was greeted like a conquering hero. Cheering crowds waved palm branches in tribute. He was hailed as the Messiah who had come to re-establish a Jewish kingdom.

The next day they returned to Jerusalem. Jesus went to the temple, the epicentre of the Jewish faith, and confronted money-changers and merchants who were ripping off the people. He overturned their tables and accused them of being thieves. The religious authorities were alarmed and feared how he was stirring up the crowds.

On the Tuesday, they challenged Jesus, questioning his authority. He answered by challenging and condemning their hypocrisy. Later that day Jesus spoke to his disciples about future times. He warned them about fake religious leaders; the coming destruction of Jerusalem; wars, earthquakes and famines; and how his followers would face persecution.

By midweek the Jewish religious leaders and elders were so angry with Jesus that they began plotting to arrest and kill him. One of Jesus’ disciples, Judas, went to the chief priests and agreed to betray him to them.

Jesus and the 12 disciples gathered on the Thursday evening to celebrate the Passover meal. This is known as the Last Supper. During the evening, Jesus initiated a ritual still marked by Christians – Holy Communion – which commemorates his death. Jesus broke bread and shared it and a cup of wine with his disciples.

Judas then left to meet the other plotters. Jesus continued to teach the others and then went outside into an olive grove to pray. He even prayed for all future believers. He agonised over what was to come but chose the way of obedience. The Bible book, Luke, records him praying, ‘Father if you are willing, take this cup from me; yet not my will but yours be done’. Minutes later Judas arrived with soldiers and the chief priests and Jesus was arrested.

9 April - Maundy Thursday: time to wash feet

Maundy Thursday is famous for two things. The first is one of the final acts that Jesus did before his death: the washing of his own disciples’ feet. (see John 13) Jesus washed his disciples’ feet for a purpose: “A new command I give you: Love one another. As I have loved you, so you must love one another.” His disciples were to love through service, not domination, of one another.

In Latin, the opening phrase of this sentence is ‘mandatum novum do vobis’. The word ‘mundy’ is thus a corruption of the Latin ‘mandatum’ (or command). The ceremony of the ‘washing of the feet’ of members of the congregation came to be an important part of the liturgy (regular worship) of the medieval church, symbolising the humility of the clergy, in obedience to the example of Christ.

But Thursday was also important because it was on that night that Jesus first introduced the Lord’s Supper, or what we nowadays call Holy Communion.

Jesus and his close friends had met in a secret upper room to share the Passover meal together - for the last time. And there Jesus transformed the Passover into the Lord’s Supper, saying, ‘this is my body’ and ‘this is my blood’ as he, the Lamb of God, prepared to die for the sins of the whole world. John’s gospel makes it clear that the Last Supper took place the evening BEFORE the regular Passover meal, and that later Jesus died at the same time that the Passover lambs were killed.

10 April - GOOD FRIDAY: the day the Son of God died for you

Luke’s account of the crucifixion (Luke 23:32-43) emphasises the mocking of the crowd, ‘If you are the king of the Jews, save yourself’ (35,37,39). In their view a Messiah does not hang on a cross and suffer. In considering the two men who was crucified with Jesus, we are also confronted with the issue of how Jesus secures salvation for us.

The words of one of those crucified with Jesus reflected the crowd’s taunts: ‘Aren’t you the Christ? Save yourself and us.’ He highlights the question of Jesus’ identity: how can He save others, when He cannot save himself from death? He failed to see that the cross itself was the means of salvation.

So - what kind of Messiah was Jesus?

The other criminal’s response in his last moments is a moving expression of faith. When challenging the other man, he spoke of the utter injustice of the crucifixion: ‘this man has done nothing wrong.’ He perceived the truth that Jesus was indeed the Messiah. In a wonderful picture of grace, ‘remember me when you come into your kingdom’, the second thief confessed his guilt and secured Jesus’ forgiveness and mercy.

In reply, Jesus promised the man life from the moment of death; ‘Today you will be with me in paradise.’ Jesus used the picture of a walled garden to help the man understand his promise of protection and security in God’s love and acceptance eternally.

Each one of us has to choose how we react to Jesus on the cross. Do we want him to ‘remember’ us when He comes into his kingdom, or not? If you were to die tonight, how confident would you be of going to be with Jesus? ‘For Christ died for sins once for all, the righteous for the unrighteous, to bring you to God.’ (1 Peter 3:18).

12 April – EASTER: the most joyful day of the year

Easter is the most joyful day of the year for Christians. Christ has died for our sins. We are forgiven. Christ has risen! We are redeemed! We can look forward to an eternity in His joy! Hallelujah!

The Good News of Jesus Christ is a message so simple that you can explain it to someone in a few minutes. It is so profound that for the rest of their lives they will still be ‘growing’ in their Christian walk with God.

Why does the date move around so much? Because the date of Passover moves around, and according to the biblical account, Easter is tied to the Passover. Passover celebrates the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt and it lasts for seven days, from the middle of the Hebrew month of Nisan, which equates to late March or early April.

Sir Isaac Newton was one of the first to use the Hebrew lunar calendar to come up with firm dates for Good Friday: Friday 7 April 30 AD or Friday 3 April, 33 AD, with Easter Day falling two days later. Modern scholars continue to think these the most likely.

Most people will tell you that Easter falls on the first Sunday after the first full moon after the Spring Equinox, which is broadly true. But the precise calculations are complicated and involve something called an ‘ecclesiastical full moon’, which is not the same as the moon in the sky. The earliest possible date for Easter in the West is 22 March, which last fell in 1818. The latest is 25 April, which last happened in 1943.

Why the name, ‘Easter’? In almost every European language, the festival’s name comes from ‘Pesach’, the Hebrew word for Passover. The Germanic word ‘Easter’, however, seems to come from Eostre, a Saxon fertility goddess mentioned by the Venerable Bede. He thought that the Saxons worshipped her in ‘Eostur month’, but may have confused her with the classical dawn goddesses like Eos and Aurora, whose names mean ‘shining in the east’. So, Easter might have meant simply ‘beginning month’ – a good time for starting up again after a long winter.

Finally, why Easter eggs? On one hand, they are an ancient symbol of birth in most European cultures. On the other hand, hens start laying regularly again each Spring. Since eggs were forbidden during Lent, it’s easy to see how decorating and eating them became a practical way to celebrate Easter.

17 March - St Patrick: beloved apostle to Ireland

St Patrick is the patron saint of Ireland. If you’ve ever been in New York on St Patrick’s Day, you’d think he was the patron saint of New York as well... the flamboyant parade is full of American/Irish razzmatazz.

It’s all a far cry from the hard life of this 5th century humble Christian who became in time both bishop and apostle of Ireland. Patrick was born the son of a town councillor in the west of England, between the Severn and the Clyde. But as a young man he was captured by Irish pirates, kidnapped to Ireland, and reduced to slavery. He was made to tend his master’s herds.

Desolate and despairing, Patrick turned to prayer. He found God was there for him, even in such desperate circumstances. He spent much time in prayer, and his faith grew and deepened, in contrast to his earlier years, when he “knew not the true God”.

Then, after six gruelling, lonely years he was told in a dream he would soon go to his own country. He either escaped or was freed, made his way to a port 200 miles away and eventually persuaded some sailors to take him with them away from Ireland.

After various adventures in other lands, including near-starvation, Patrick landed on English soil at last, and returned to his family. But he was much changed. He had enjoyed his life of plenty before; now he wanted to devote the rest of his life to Christ. Patrick received some form of training for the priesthood, but not the higher education he really wanted.

But by 435, well-educated or not, Patrick was badly needed. Palladius’ mission to the Irish had failed, and so the Pope sent Patrick back to the land of his slavery. He set up his see at Armagh, and worked principally in the north. He urged the Irish to greater spirituality, set up a school, and made several missionary journeys.

Patrick’s writings are the first literature certainly identified from the British Church. They reveal sincere simplicity and a deep pastoral care. He wanted to abolish paganism, idolatry, and was ready for imprisonment or death in the following of Christ.

Patrick remains the most popular of the Irish saints. The principal cathedral of New York is dedicated to him, as, of course, is the Anglican cathedral of Dublin.

1 March - St David’s Day: time for daffodils

1st March is St David’s Day, and it’s time for the Welsh to wear daffodils or leeks. Shakespeare called this custom ‘an honourable tradition begun upon an honourable request’ - but nobody knows the reason. Why should anyone have ever ‘requested’ that the Welsh wear leeks or daffodils to honour their patron saint? It’s a mystery!

We do know that David - or Dafydd - of Pembrokeshire was a monk and bishop of the 6th century. In the 12th century he was made patron of Wales, and he has the honour of being the only Welsh saint to be canonised in the Western Church. Tradition has it that he was austere with himself, and generous with others - living on water and vegetables (leeks, perhaps?!) and devoting himself to works of mercy. He was much loved.

In art, St David is usually depicted in Episcopal vestments, standing on a mound with a dove at his shoulder, in memory of his share at an important Synod for the Welsh Church, the Synod of Brevi.

14 February - Valentine’s Day

There are two confusing things about this day of romance and anonymous love-cards strewn with lace, cupids and ribbon: firstly, there seems to have been two different Valentines in the 4th century - one a priest martyred on the Flaminian Way, under the emperor Claudius, the other a bishop of Terni martyred at Rome. And neither seems to have had any clear connection with lovers or courting couples.

So why has Valentine become the patron saint of romantic love? By Chaucer’s time the link was assumed to be because on these saints’ day -14 February - the birds are supposed to pair. Or perhaps the custom of seeking a partner on St Valentine’s Day is a surviving scrap of the old Roman Lupercalia festival, which took place in the middle of February.

One of the Roman gods honoured during this Festival was Pan, the god of nature. Another was Juno, the goddess of women and marriage. During the Lupercalia it was a popular custom for young men to draw the name of a young unmarried woman from a name-box. The two would then be partners or ‘sweethearts’ during the time of the celebrations. Even modern Valentine decorations bear an ancient symbol of love - Roman cupids with their bows and love-arrows.

There are no churches in England dedicated to Valentine, but since 1835 his relics have been claimed by the Carmelite church in Dublin.

14 February - The very first Valentine card: a legend

The Roman Emperor Claudius II needed soldiers. He suspected that marriage made men want to stay at home with their wives, instead of fighting wars, so he outlawed marriage.

A kind-hearted young priest named Valentine felt sorry for all the couples who wanted to marry, but couldn’t. So secretly he married as many couples as he could - until the Emperor found out and condemned him to death. While he was in prison awaiting execution, Valentine showed love and compassion to everyone around him, including his jailer. The jailer had a young daughter who was blind, but through Valentine’s prayers, she was healed. Just before his death in Rome on 14 February, he wrote her a farewell message signed ‘From your Valentine.’

So, the very first Valentine card was not between lovers, but between a priest about to die, and a little girl, healed through his prayers.

1 January - The Naming of Jesus

It is Matthew and Luke who tell the story of how the angel instructed that Mary’s baby was to be named Jesus - a common name meaning ‘saviour’. The Church recalls the naming of Jesus on 1 January - eight days after 25 December (by the Jewish way of reckoning days). For in Jewish tradition, the male babies were circumcised and named on their eighth day of life.

For early Christians, the name of Jesus held a special significance. In Jewish tradition, names expressed aspects of personality. Jesus’ name permeated His ministry, and it does so today: we are baptised in the name of Jesus (Acts 2:38), we are justified through the name of Jesus (1 Cor 6:11); and God the Father has given Jesus a name above all others (Phil 2:9). All Christian prayer is through ‘Jesus Christ our Lord’, and it is ‘at the name of Jesus’ that one day every knee shall bow.

The History of Christmas

The Bible does not give a date for the birth of Jesus. In the third century it was suggested that Jesus was conceived at the Spring equinox, 25th March, popularising the belief that He was born nine months later on 25th December. John Chrysostom, the Archbishop of Constantinople, encouraged Christians worldwide to make Christmas a holy day in about 400.

In the early Middle Ages, Christians celebrated a series of midwinter holy days. Epiphany (which recalls the visit to the infant Jesus of the wise men bearing gifts) was the climax of 12 days of Christmas, beginning on 25th December. The Emperor Charlemagne chose 25th December for his coronation in 800, and the prominence of Christmas Day rose. In England, William the Conqueror also chose 25th December for his coronation in 1066, and the date became a fixture both for religious observance and feasting.

Cooking a boar was a common feature of mediaeval Christmas feasts, and singing carols accompanied it. Writers of the time lament the fact that the true significance of Christmas was being lost because of partying. They condemn the rise of ‘misrule’ – drunken dancing and promiscuity. The day was a public holiday, and traditions of bringing evergreen foliage into the house and the exchange of gifts (usually on Epiphany) date from this time.

In the 17th century the rise of new Protestant denominations led to a rejection of many celebrations that were associated with Catholic Christianity. Christmas was one of them. After the execution of Charles I, England’s Puritan rulers made the celebration of Christmas illegal for 14 years. The restoration of Charles II ended the ban, but religious leaders continued to discourage excess, especially in Scotland. In Western Europe (but not worldwide) the day for exchanging gifts changed from Epiphany (6th January) to Christmas Day.

By the 1820s, there was a sense that the significance of Christmas was declining. Charles Dickens was one of several writers who sought to restore it. His novel A Christmas Carol was significant in reviving merriment during the festival. He emphasised charity and family reunions, alongside religious observance. Christmas trees, paper chains, cards and many well-known carols date from this time. So did the tradition of Boxing Day, on 26th December, when tradesmen who had given reliable service during the year would collect ‘boxes’ of money or gifts from their customers.

In Europe Santa Claus is the figure associated with the bringing of gifts. Santa Claus is a shortening of the name of Saint Nicholas, who was a Christian bishop in the fourth century in present-day Turkey. He was particularly noted for his care for children and for his generosity to the poor. By the Middle Ages his appearance, in red bishop’s robes and a mitre, was adored in the Netherlands and familiar across Europe.

Father Christmas dates from 17th century England, where he was a secular figure of good cheer (more associated with drunkenness than gifts). The transformation of Santa Claus into today’s Father Christmas started in New York in the 1880s, where his red robes and white beard became potent advertising symbols. In some countries (such as Latin America and Eastern Europe) the tradition attempts to combine the secular and religious elements by holding that Santa Claus makes children’s presents and then gives them to the baby Jesus to distribute.

6th December: St Nicholas – a much-loved saint

One account of how Father Christmas began tells of a man named Nicholas who was born in the third century in the Greek village of Patara, on what is today the southern coast of Turkey. His family were both devout and wealthy, and when his parents died in an epidemic, Nicholas decided to use his inheritance to help people. He gave to the needy, the sick, the suffering. He dedicated his whole life to God’s service and was made Bishop of Myra while still a young man. As a bishop in later life, he joined other bishops and priests in prison under the emperor Diocletian’s fierce persecution of Christians across the Roman Empire.

Finally released, Nicholas was all the more determined to shed abroad the news of God’s love. He did so by giving. One story of his generosity explains why we hang Christmas stockings over our mantelpieces today. There was a poor family with three daughters who needed dowries if they were to marry, and not be sold into slavery. Nicholas heard of their plight and tossed three bags of gold into their home through an open window – thus saving the girls from a life of misery.

The bags of gold landed in stockings or shoes left before the fire to dry. Hence the custom of children hanging out stockings – in the hope of attracting presents of their own from St Nicholas - on Christmas Eve. That is why three gold balls, sometimes represented as oranges, are one of the symbols of St Nicholas.

The example of St Nicholas has never been forgotten - in bygone years boys in Germany and Poland would dress up as bishops on 6th December, and beg alms for the poor. In the Netherlands and Belgium ‘St Nicholas’ would arrive on a steamship from Spain to ride a white horse on his gift-giving rounds. To this day, 6th December is still the main day for gift-giving and merry-making in much of Europe. Many people feel that simple gift-giving in early Advent helps preserve a Christmas Day focus on the Christ Child.

Experience the Joy of Advent

‘Fear not: for behold I bring you good tidings of great joy, which shall be to all people.’ Luke 2:10

Advent starts on the fourth Sunday before Christmas. The word ‘Advent’ is from the Latin word ‘adventus’ meaning ’coming’. Sometimes called ‘Little Lent’, it’s a time to prepare our hearts for the future Second Coming, as well as the birth of Christ.

We celebrate the season with advent calendars, candles and evergreen wreaths - symbolising Christ as Light of the world, bringing new and everlasting life.

Here are seven simple tips to help you experience and share the joy of Advent!

1. Connect with your inner child: Think back to the time when you were a child, on the simple things that made you happy at Christmas. Focus only on the good and feel the joy of Christmas come flooding back!

2. Keep it simple: This year, go for gifts and cards that share the meaning of the season, shop early and stay within your budget.

3. Be people focused: Remember the story of Mary and Martha – keep meals simple and allow yourself time and space to focus on enjoying the company of your guests.

4. Make Room for Jesus: Take some time at the beginning of each day to read your Bible, meditate on Scripture and pray. Focus on giving thanks to God for His gift of Christ to the world and for all He has done for us.

5. Me Time: God wants us to prosper in body, soul and spirit, so try to eat healthy, don’t overindulge, take time for long walks and enjoy the good and simple things in life!

6. Wear a smile and share the Joy! Finally, being joyful is a choice, it’s not about your circumstances. So, decide to be thankful this season. Wear a smile, act and talk positively, do small things with great love, be on the lookout for opportunities to do good to people. Give to the homeless, visit the sick, or take gifts to lonely neighbours.

If people ask you about your joy, don’t be afraid to share your faith. Simply explain to them that ‘Christ lives in my heart, and He can live in yours too.’

30 November Andrew - first disciple of Jesus

Andrew, whose feast day ends the Christian year on 30th November, is probably best known to us as the patron saint of Scotland, though his only connection with the country is that some of his bones were reputedly transported in the 8th century to Fife and preserved at a church in a place now named St Andrews.

In fact, there are so many legends about him all over Europe and the Middle East that it’s safest to stick to what the Gospels tell us - though the strong tradition that he was martyred by crucifixion is probably true and is perpetuated in the ‘St Andrew’s Cross’, the ‘saltyre’ of Scotland.

The Gospels record that he was one of the first disciples of Jesus, and the very first to bring someone else to Christ - his own brother. Like many fervent Jews at the time Andrew and an unnamed companion had been drawn to the desert, to be taught by the charismatic prophet known to us as John the Baptist. Many thought that he was the long-promised Messiah, but John insisted that he was not. ‘I am the voice crying in the wilderness,’ he told the crowds. ‘Prepare the way of the Lord! One comes after me who is greater than I am.’ So when one day John pointed out Jesus to Andrew and his friend and described him as the ‘Lamb of God’, the two young men assumed that the next stage of their spiritual search was about to unfold. So as Jesus made off, they followed him.

All the more strange, then (though, on reflection, very true to human nature) that when Jesus turned and asked them what they were ‘seeking’, all they could come up with was a lame enquiry about his current place of residence: ‘where are you staying?’ Or, perhaps, they were hinting that what they were seeking could not be dealt with in a brief conversation. If they could come to his lodgings, perhaps their burning questions might be answered.

The reply of Jesus was the most straight-forward invitation anyone can receive: ‘Come and see’. Come and see what I’m like, what I do, the sort of person I am. What an invitation!

The results of their response were in this case life-changing - for themselves, and for many other people. Andrew brought his brother, Peter, to Jesus. The next day Jesus met Philip and called him to ‘follow‘. Philip then brought Nathaniel. The little apostolic band who would carry the message of Jesus to the whole world was being formed. They came, they saw, they were conquered! And right at the front of the column, as it were, was Andrew, the first disciple of Jesus.

1st November: All Saints’ Day – the feast day of all the redeemed

All Saints, or All Hallows, is the feast of all the redeemed, known and unknown, who are now in heaven. When the English Reformation took place, the number of saints in the calendar was drastically reduced, with the result that All Saints’ Day stood out with a prominence that it had never had before.

This feast day first began in the East, perhaps as early as the 5th century, as commemorating ‘the martyrs of the whole world’. A Northern English 9th century calendar named All Hallows as a principal feast, and such it has remained. Down the centuries devotional writers have seen in it the fulfilment of Pentecost and indeed of Christ’s redemptive sacrifice and resurrection.

The saints do not belong to any religious tradition, and their lives and witness to Christ can be appreciated by all Christians. Richard Baxter, writing in the 17th century, wrote the following:

He wants not friends that hath thy love,

And made converse and walk with thee,

And with thy saints here and above,

With whom for ever I must be...

As for my friends, they are not lost;

The several vessels of thy fleet,

Though parted now, by tempests tost,

Shall safely in thy haven meet....

The heavenly hosts, world without end,

Shall be my company above;

And thou, my best and surest Friend,

Who shall divide me from thy love?*

1,255 ancient English churches were dedicated to All Saints - a number only surpassed by those dedicated to the Virgin Mary.

*(Maurice Frost (ed.), Historical Companion to Hymns Ancient and Modern (London: Clowes, 1962), no. 274, verses 1,3,6.

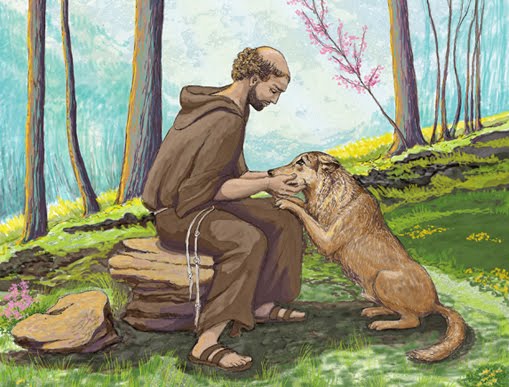

St Francis of Assisi - love for the Creation

St Francis (1181 - 1226) is surely one of the most attractive and best-loved of all the saints. But he began by being anything but a saint. Born the son of a wealthy cloth-merchant of Assisi, Francis’ youth was spent in fast-living, parties and on fast horses as a leader of the young society of the town. Then he went to the war between Assisi and Perugia, and was taken prisoner for a year.

By the time of his release, Francis had changed. Perhaps his own suffering had awakened him to that of others. In any case, he abandoned warfare and carousing, and began to help the poor and the lepers of his area. Then one day a voice which seemed to come from the crucifix in the small, semi-derelict church of Damiano Assisi ‘Go and repair my house, which you see is falling down’.

This religious experience was a vital turning point in Francis’ life: Jesus Christ became very real and immediate to him. His first action was to begin repairing the church, having sold some of his father’s cloth to pay for materials. His father was not amused, in fact he was furious - until Francis renounced his inheritance and even his clothes by his dramatic stripping off in the public square of the town. The Bishop of Assisi provided him with simple garments, and Francis began his new life.

His inspiration was always religious, not social, and the object of his quest was always the Crucified Christ, not Lady Poverty for her own sake. Francis rebuilt San Samiano, and then travelled as a pilgrim. His compassion for the poor and lepers became famous. Soon disciples joined him, and they set up a communal life in simple wattle and daub huts. They went on occasional preaching tours. (Not until later did they become an Order whose theologians won fame in the Universities.)

In 1219 Francis visited the Holy Land, and his illusions about the Crusaders were shattered. He went on to seek out the Sultan, and tried to convert him. Back home, he found his Order was now 5,000 strong, and growing. Francis stepped down as head, but continued to preach and was immensely popular. He died after a prolonged illness at the age of 45, and was canonised in 1228.

Francis’ close rapport with the animal creation was well known. The story of his preaching to the birds has always been a favourite scene from his life. He also tamed the wolf of Gubbio. This affinity emphasises his consideration for, and sense of identity with, all elements of the physical universe, as seen in his Canticle of the Sun. This makes him an apt patron of nature conservation.

The 20th century witnessed a widespread revival of interest in Francis. Sadly, some films and books caricatured him as only a sentimental nature-lover or a hippie drop out from society. This ignores the real sternness of his character, and his all-pervasive love of God and identification with Christ’s sufferings, which alone make sense of his life. Two ancient, and many modern English churches are dedicated to him.

27th Sept Vincent de Paul – patron of all charitable societies

Very few people stand out as being incredibly good, but Vincent de Paul was one of them. His life touched thousands of people, who were helped and inspired by his love and kindness.

Vincent de Paul was born in 1581 to a Gascon peasant family at Ranquine. Educated by the Franciscans and then at Toulouse University, he was ordained a priest very young, at only 19. He became a court chaplain, and then tutor to the children of the Gondi family. In 1617 he was made parish priest of Chatillon-les-Dombes.

From here, Vincent de Paul ministered both to the rich and fashionable, and also to the poor and oppressed. He helped prisoners in the galleys, and even convicts at Bordeaux.

In 1625 Vincent de Paul founded a congregation of priests who renounced all church preferment and instead devoted themselves to the faithful in smaller towns and villages. In 1633 they were given the Paris priory church of Saint-Lazare, and that same year Vincent founded the Sisters of Charity, the first congregation of ‘unenclosed’ women, whose lives were entirely devoted to the poor and sick, and even providing some hospital care. Rich women helped by raising funds for various projects, which were an immense success.

Even in his lifetime, Vincent became a legend. Clergy and laity, rich and poor, outcasts and convicts all were warmed and enriched by his charisma and selfless devotion. Vincent was simply consumed by the love of God and of his neighbour. His good works seemed innumerable – ranging from helping war-victims in Lorraine, and sending missionaries to Poland, Ireland and Scotland, to advising Anne of Austria at Court during the regency.

No wonder that after his death at nearly 80, the Pope named him as patron of all charitable societies. Even today, the Vincent de Paul Society is working with the poor and oppressed.

16th Sept St. Cornelius – the saint who had mercy on sinning Christians

Have you ever sinned since you became a Christian? Really sinned – or in other words done something that was SO wrong and totally ‘out of line’ with being a Christian that you are still ashamed when you think of it now. If so, and if you went on to ask God’s forgiveness for it, and have resolved never to do it again, then Cornelius is a good saint for you. He fought for Christians who had failed miserably to be given a second chance.

The time was 251, and Cornelius had just become Bishop of Rome. The Church at this time was struggling with what to do about Christians who had lapsed, and who now wanted to come back. Novation, a powerful Roman priest, argued that the Church had no power to pardon and welcome back any Christian who had caved in under persecution, or who had committed adultery or murder or similar serious offences.

Cornelius disagreed, and said that if a Christian truly repented and did the appropriate penance to prove it, then they should eventually be admitted back into the Church. The argument might sound over-earnest to modern ears, but it reflects how seriously the early Christians took their commitment to follow Jesus in leading a holy life, and in being willing to die for Him. In the end, that is exactly what Cornelius did – accepted death as the next persecution began, rather than deny Him.

1st September: St. Drithelm - vision of the after-life

Drithelm is the saint for you if you have ever wondered what lies beyond death, or have had a near-death experience. He was married and living in Cunningham (now Ayrshire, then Northumbria) in the 7th century when he fell ill and apparently died. When he revived a few hours later he caused panic among the mourners, and was himself deeply shaken by the whole experience.

Drithelm went to pray in the village church until daylight, and during those long hours reviewed the priorities of his life in the light of what he had seen while ‘dead’. A celestial guide had shown him souls in hell, in purgatory, in paradise and heaven... suddenly the reality of God and of coming judgement and of what Christ had done in redeeming mankind became real to him, and his life on earth could never be the same again.

Next day he divided his wealth into three: giving one third to his wife, one third to his sons, and the remainder to the poor. He became a monk and went to live at Melrose, where he spent his time in prayer and contemplation of Jesus.

Drithelm’s Vision of the after-life is remarkable in that it was the first example of this kind of literature from England. It was SO early: seventh century Anglo-Saxon England! Drithelm has even been seen as a remote precursor of Dante.

On a lighter note, Drithelm can also be a saint for you if you didn’t get abroad this summer, but ventured to swim instead off one of our beaches: he used to stand in the cold waters of the Tweed for hours, reciting Psalms.

The Rev Paul Hardingham considers the miracle of The Transfiguration, which is remembered by the Church on 6th August.

The Transfiguration – seeing Jesus as He is

The title of Bob Geldof’s autobiography, ‘Is That It?’, will resonate with us, when we’re looking for more in life. On a deeper level, we want to see and hear more clearly what God is doing in our circumstances. Jesus’ transfiguration, which we remember this month, helps us to consider this (Luke 9:28-36).

Jesus was transfigured alongside Moses and Elijah, ‘As He was praying, the appearance of His face changed, and His clothes became as bright as a flash of lightning.’ (29). To understand our circumstances, firstly we need to see Jesus as God wants us to see Him. The disciples’ eyes were opened to see Jesus’ divinity. The presence of Moses and Elijah confirmed Him as God’s promised Messiah. By foreshadowing the resurrection, this event powerfully calls us to entrust our lives into Jesus’ hands to experience His presence and power.

Secondly, if we are to make sense of our circumstances, we need to hear what God says about His Son. A cloud covered them and ‘a voice came from the cloud, saying, ‘This is my Son, whom I have chosen; listen to Him.” (35). God affirmed His love and call on Jesus as His beloved and chosen Son. Do we hear God speaking these same words to us? When we know that we too are loved and accepted by God, this transforms our understanding of our lives.

Whatever our circumstances, they can be transformed by what we see and hear. Open your eyes to see a transfigured world. Open your ears to hear a transfiguring voice. Open your heart to become a transfigured life.

‘Christians should see more clearly, because we have seen Jesus. We are people whose vision has been challenged and corrected, so that we can see the world as it properly is.’ (Justin Welby).